Διαβάστε τη συνέντευξη που παραχώρησα στο περιοδικό GOLD για την έκδοση Μαΐου 2021, η οποία ήταν αφιερωμένη στη Λεμεσό.

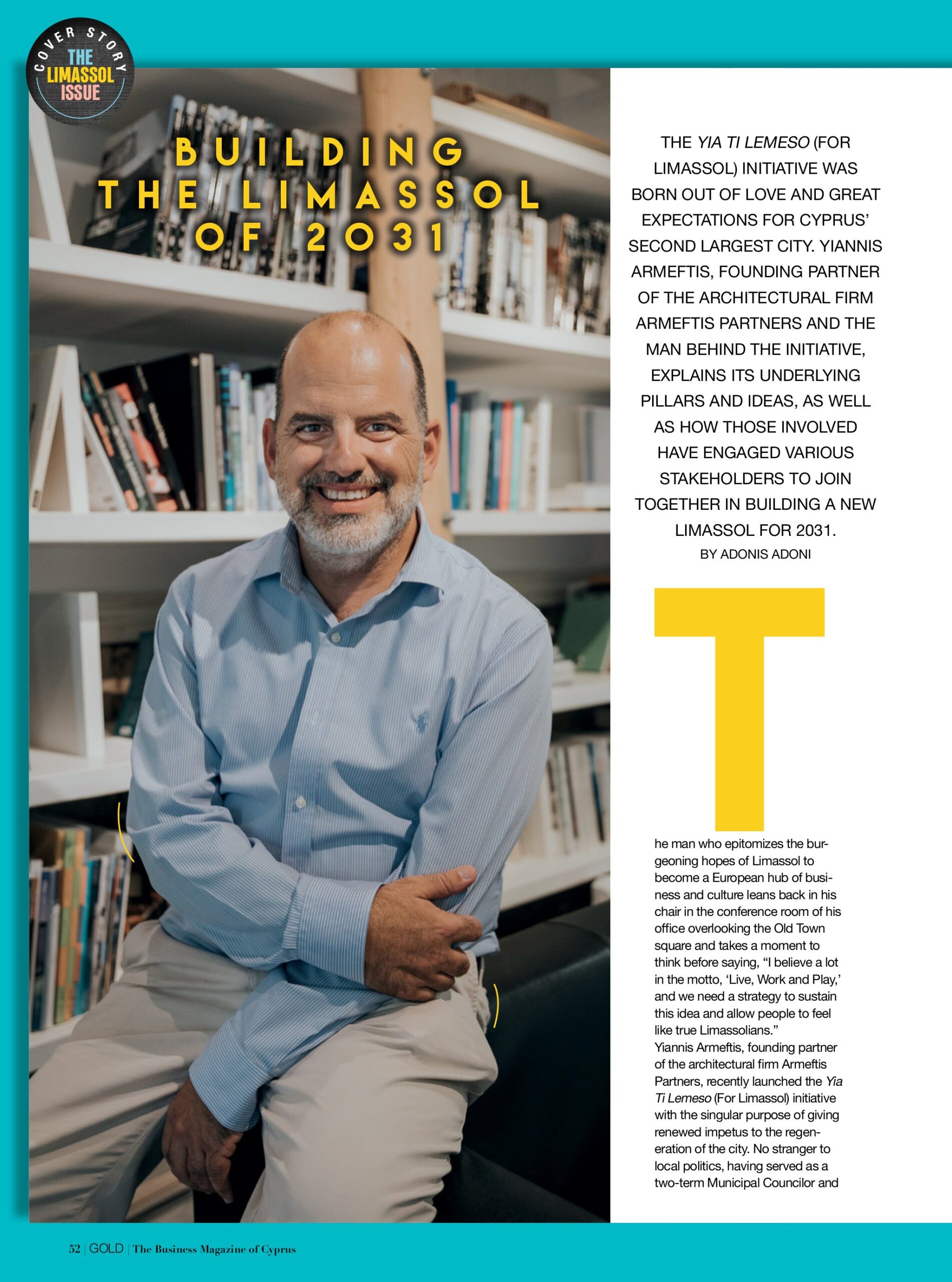

THE YIA TI LEMESO (FOR LIMASSOL) INITIATIVE WAS BORN OUT OF LOVE AND GREAT EXPECTATIONS FOR CYPRUS’ SECOND LARGEST CITY. YIANNIS ARMEFTIS, FOUNDING PARTNER OF THE ARCHITECTURAL FIRM ARMEFTIS PARTNERS AND THE MAN BEHIND THE INITIATIVE, EXPLAINS ITS UNDERLYING PILLARS AND IDEAS, AS WELL AS HOW THOSE INVOLVED HAVE ENGAGED VARIOUS STAKEHOLDERS TO JOIN TOGETHER IN BUILDING A NEW LIMASSOL FOR 2031.

By Adonis Adoni

The man who epitomizes the burgeoning hopes of Limassol to become a European hub of business and culture leans back in his chair in the conference room of his office overlooking the Old Town square and takes a moment to think before saying, “I believe a lot in the motto, ‘Live, Work and Play,’ and we need a strategy to sustain this idea and allow people to feel like true Limassolians.”

Yiannis Armeftis, founding partner of the architectural firm Armeftis Partners, recently launched the Yia Ti Lemeso (For Limassol) initiative with the singular purpose of giving renewed impetus to the regeneration of the city. No stranger to local politics, having served as a two-term Municipal Councilor and Chairman of the Development Committee under Mayor Andreas Christou, he saw at first hand the tremendous upside of bringing government and capital together. He believes that the brisk pace of construction of Limassol Marina – completed much faster than many major projects in other Cyprus cities – can be traced to the synergy between the Limassol Municipality, the Government and the Limassol Chamber of Commerce & Industry. The same can be said of the establishment in Limassol of the state-owned Cyprus University of Technology (CUT) and the growth of the local shipmanagement industry into EU’s largest centre.

“We started having talks with various stakeholders to understand the problems they face and how they relate to the city. We were invited to an event held by Tech Island, we had talks with the CUT, with people in the arts and culture,” he says. Tech Island is a newly formed association of some of the biggest international companies that have relocated part of their business to Cyprus and some 80% of its members are based in Limassol. Indeed, for many people, including Armeftis, the geographical battle for the eyes of foreign investors has entered a new chapter; it’s now all about the city. “No-one can deny that there are tax benefits in coming to Cyprus but these companies also believe in Limassol because they see that the city has potential,” he notes.

For Armeftis, unless the objective is to dishearten foreign investors, the bureaucratic web must become untangled and regulations – the main source of unwanted delays – must be drafted in such a way as to avoid multiple interpretations. Some steps in this direction have already been taken: in 2020, in one of her first acts at the Ministry of Energy, Commerce & Industry, Natasa Pilides announced a new fast-track business activation mechanism, while the multi-prong strategy of Invest Cyprus, the country’s investment promotion agency, has introduced a new and simpler immigration framework for tech companies. On paper, there is also a lot of movement at local government level to cut down on bureaucracy, with a blockchain-enabled solution for marriage certificates and the Dimotis Lemesou (Limassol Citizen) app, to name a few. However, the fact that people still lambast the local authority about the headache-inducing morass of red tape, even at the very basic level of e-mail communications, suggests that a lot of work remains to be done.

Living in Limassol can be unreasonably expensive – apartment prices are the highest in Cyprus, which prompted the sprouting of placards in a large protest outside the Municipality in 2018. Armeftis brings his fingers together and says, “We have to take into account the particularities of the city. Almost half of the buildings in the Old Town square are abandoned – there is a lot of room for restoration here.” Allowing these properties to re-enter the market might prove a better alternative way of increasing supply over demand than the current plans to inject the city with new units. A new development project, co-signed by the Limassol Municipality and the Cyprus Land Development Committee (CLCD) to build 600 affordable houses does not leave Armeftis particularly impressed. He explains why: the previous collaboration between the Municipality and the CLDC – 10 years ago, with a housing project in the Franklin Roosevelt Avenue area – was successful because the housing units were given to people in need based on certain criteria. However, the new project seems to be built on an exchange system, with the Municipality taking the role of the administrator. “I just don’t believe they have the capability to do so,” he says. High on the Yia Ti Lemeso list of priorities is the development of networks and infrastructures that will allow the city to become more accessible, following the model of the 15-minute city. “I believe that cars should be excluded from the city centre,” he says. The initiative proposes the creation of alternative routes – bikeways and walkways – and it recently held an event to which experts from abroad were invited to discuss the impact of tramways in small cities across Europe. Armeftis appears certain about the feasibility of an electric tram system that connects the city. For this idea to work, he goes on, areas near the planned casino and the new passenger terminal would be turned into large parking spaces, while developing a linear park along the way that passes through the Karnayio (Limassol’s former shipyard) area would provide Limassolians with a scenic walking alternative as they go about their business. As a backbone to these alternative routes, the initiative proposes a network that connects the ancient cities of Amathus (east of the city) and Kourion (west of the city). One-way arteries splintering off this main road would turn into green routes, which, according to Armeftis, would be more useful than the green neighbourhoods planned by the local authority.

To engage citizens in building the Limassol of 2031, the initiative has launched the Discord app, which lets people to share their opinions, and the Calendly app, with which anyone can book an appointment to better understand the ideas and plans of Yia Ti Lemeso. On top of that, the initiative has already conducted a survey, in collaboration with Insight Market Research (University of Cyprus), in which 600 Limassol residents were asked for their opinions on various issues related to their city. It doesn’t come as a surprise that, in the minds of the majority, the city’s identity is reflected in the coastal front with the Seaside Park and the Limassol Marina. “This shows these projects were successful, but it also tells us that other public spaces are severely underdeveloped,” Armeftis notes. Respondents also named the lack of green areas as a major issue. At the moment, there is 1.8m² green per capita in the city and the initiative plans to take it up to 11m² by 2031. “And we want culture and art to be the pillars of a future Limassol,” Armeftis notes.

Yia Ti Lemeso has its work cut out. Urban development and social change require serious investment and EU funding programmes – Horizon, European Funds Unit, etc. – must be exploited to that effect. While Cyprus appears to have edged ahead of other EU member states in securing more money than it has contributed to the Horizon 2020 programme, there remains a question mark over Limassol’s resolve to assert its claim in these funds. Particularly instructive is the fact that in 2018, the Limassol Chamber of Commerce & Industry was a participant in the Horizon 2020-funded project to build a Marine and Maritime Research, Innovation, Technology Centre of Excellence, which was built not in Limassol but in Larnaca. On the plus side, the bottom-up approach of the initiative to include citizens in the conversation has enjoyed great success in the urban redevelopment of large cities across the world. After all, as Shakespeare asks in Coriolanus, “What is a city but the people?”